A few weeks ago, my grandfather passed away—my father’s father, whom I called Grandpop. I was there with him when he died. I’d arrived at his bedside just hours earlier, after traveling from the west to the east coast and then to the toy-like town in New Hampshire where he’d lived as long as I’d known him. Grandpop was half-asleep and breathing with difficulty, his hands moving boxily from blankets to his face and then back again, reaching for or adjusting something I couldn’t see. He was clearly very ill, but I hardly expected this to be among his final moments. What are the chances that I would roll up just in time to say goodbye? Plus, even in his state, he was as stubborn and willful as he’d always been. A few minutes into a hushed conversation with my Uncle Larry, Grandpop (also known as Gordon) shot Larry a familiar side-eyed look. “He may be on death’s door, but I’d recognize that baleful glance from anywhere,” my uncle said wryly. We took our hushed conversation outside Grandpop’s room, where I noticed a handwritten sign was taped to his door: “QUIET, PLEASE. (By request of Gordon.)”

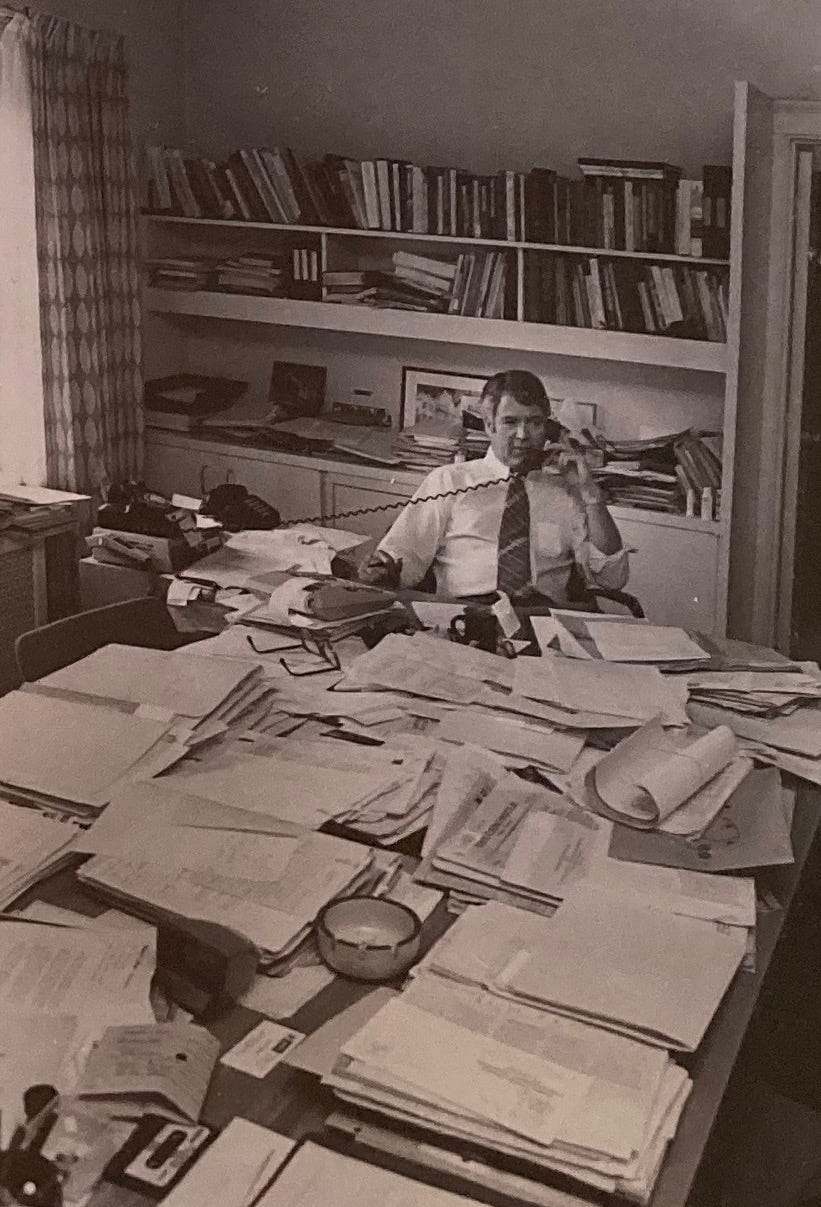

For my whole life, Grandpop been an imposing figure: regal and stern in a way I’d only encountered in those of his generation—and surely class played a part, too. Visiting him and my Gran as a kid meant briefly inhabiting the New England WASP culture from which I felt far removed, but which I also knew sponsored my immediate family’s financial safety net. I did relish my temporary immersion in my grandparents’ world, with all its luxuries big and small—fresh squeezed orange juice in the mornings, an actual lakeside cottage. But even when I was physically present, Grandpop was a remote figure. I picture him in a button-up shirt with a tumbler glass full of vermouth keeping his distance from the rowdy congregation of cousins that my generation formed. If we got too loud, he communicated displeasure with the authoritative glare that Larry picked up on in an instant. He was also kind and generous, but he was definitely an enigma. Phone conversations with him were notoriously brief—these friendly but diplomatic and elliptical exchanges.

He was 92 years old when I saw him this month, which is also to say he was 92 when he died. His body had been re-sculpted by the cancer formally diagnosed only two weeks earlier, his face worn away into a leaner outline and his abdomen swollen. It did not scare me to see him like that, but that vulnerability unleashed a torrent of tenderness that caught me by surprise. He retained his dignified personality but his sweetness was laid more plain and bare beneath it. Shortly before he passed away, Grandpop flickered awake, and when he saw me, his face lit up. I will be forever grateful to have been able to exchange that look with him—to travel to the other end of the continent and to the end of his life, and to express mutual love with a plainness or directness I don’t recall experiencing with him before.

I’d felt that tenderness before, and I’m glossing over all kinds of sweet moments as well as the nuances that really comprise my Grandpop. (One of the sweetest parts of his story is that, after my grandmother passed away, he found love and enjoyed six happy years with his second wife Betty, whom he adored deeply.) But my final goodbye to him newfound unleashed tenderness, and in the days that have followed his death I’ve been crying like I’m making up for lost time.

That may just be what I’m crying for, or what drives it—a fact of affection that’s welled up for nearly a lifetime. I cried over photo albums and the shirts in his closet. I cried learning more about my him from people I hadn’t met yet who spoke at the funeral and from my relatives who I haven’t seen for years. This collective stream of narrative and facts augmented my understanding of who he was. I cried to recognize parts of myself and other relatives in this newly expanded portrait. I cried because his wife Betty had to say goodbye to him, too. I cried leaving his house before flying back west, bidding a final farewell to the midcentury modern scenery, the gross basement, and the trees. Now I cry walking in the woods with my dog because it is private and I guess being alone there reminds me that I’ve lost someone I never fully knew, and this loss reminds me of the disconnection that runs through the generations in my family. I cry remembering my father’s hand next to but not touching his father’s hand on the sick bed, and how I mirrored that gap in my own hesitation next to my father. I cry because I watched my father lose his father and I didn’t know how to comfort him. Instead, I took his restrained reaction at face value and didn’t try to penetrate the emotional shield passed down the patrilineal line. I cry about how this patrilineal line is also, indelibly, foundational to my existence. Without it, I am not here; with it, I have the gift of life and a complicated inheritance.

Grief conjugates happy memories and other residues into a singular tear-jerking swirl. It also colors outside its contour lines with bittersweet heaviness (and weirdly also an effervescent levity). Though it has a specific object, the radius of my grief extends beyond its nucleus; I feel kinship with the whole world and tenderness toward the past and future.

That I’m inclined to be this dramatically sentimental has always set me apart from the side of my family (and the ancestor) I’m currently grieving. I felt it as a kid, and I felt it as an adult. (I was among the most teary-eyed at the funeral.) For so much of my life, the ways that I’m different from my family—on all sides, really—has been a source of pride, a thread around which I’ve wrapped my identity. It’s easy for me to quickly leap from that nucleus of grief to its wider berth—that more generalized expanse of tenderness that forms around it. I do love the ways that grief locates me in a web of connection, where a singular loss exposes the care patterned throughout my life. But there’s a funny mirroring between the kind of disassociation that happens when I leap from my specific grief to a generalized sense of it, and then the relative coolness I’ve often experienced in (and brought to) my family. They are related to each other, a positive feedback loop of fictional distance.

Somehow this whole experience has forced me to face certain contradictions (or tensions) I’ve long known, but which never quite felt high-stakes: How to be in the family and also myself. How to let my difference bring me closer, and also how to not push away (or deny) the ways I’m not so different. How to honor what and who came before while also reckoning with their more difficult aspects. I could keep listing them, but I think the biggest tension I feel has to do with how I see myself, and with letting all of my lineages inform that narrative—lineages I’d thought were merely incidental, but grief tells me otherwise. It speaks a desire to belong to that which can never hold all of me, but without which I wouldn’t be who I am at all.

If you enjoy reading this newsletter and are so inclined, sharing it with a friend or hitting the “like” button are great ways to support my work. I also really love hearing from readers. Just hit reply and your message will land in my inbox. Thank you for reading and for being here!

My website — Learn more about my work

Experimental Practice podcast — Conversations about cross-genre and interdisciplinary work, culture, writing craft, and creative practice

Follow me on Instagram — I’m there sometimes

Read more Essence of Toast — Archive of past letters

Lovely piece! ❤️

What a beautiful reflection and tribute, Siloh, both to your Grandpop and to your own journey. <3